Henry Louis Taylor Jr. | Charlotte Hsu

BUFFALO, N.Y. — I recently sat down to talk about Buffalo’s East Side with Henry Louis Taylor Jr., director of the University at Buffalo’s Center for Urban Studies and a man with an impressive collection of maps, books and Census records documenting the city’s history. I asked him, specifically, how Broadway-Fillmore, a once-bustling neighborhood deep in East Buffalo, came to be one of the nation’s poorest areas.

Here’s a synopsis, based on what he said and information cobbled together from other sources:

Older residents recall Broadway-Fillmore as Buffalo’s old Polonia — a thriving, working-class community centered around factories and the railroad. The district was home to the Central Terminal, the city’s main train station and an architectural wonder with an office tower 17 stories tall. Broadway Street was a destination for shoppers looking to buy everything from pastries to jewelry, clothing and shoes.

Taylor says the community began to change in the post-World War II era with the development of the Interstate Highway System and the commodification of housing, which increased people’s mobility and catalyzed the development of suburbs across the nation. In Buffalo, families who owned homes in Broadway-Fillmore began to move to Cheektowaga and similar communities, drawn by the promise of an idealized, suburban lifestyle.

What they left behind | Charlotte Hsu

The exodus coincided with several important historical events, one being an explosion in Buffalo’s African American population. Between 1940 and 1970, Taylor says, the number of black residents in the city rocketed from 17,000 to close to 100,000. Much of that increase resulted from the Second Great Migration — the mass migration of African Americans from the country’s segregated South to urban areas in the industrialized North, Midwest and West.

These economic migrants arrived in Buffalo at a time when urban renewal projects were pushing African Americans out of their traditional neighborhoods — which had been ethnically integrated — and into sectors of the city that whites were vacating. Thousands of these displaced people, many very poor, made their way into Broadway-Fillmore starting in the late 1960s, drawn by low rents, Taylor says.

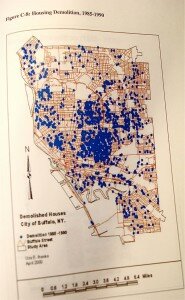

A map of demolitions between 1985 and 1990 | Charlotte Hsu

Despite this influx, many abandoned homes remained vacant. Factories that once employed East Side laborers were closing. The last train departed from the Central Terminal on Oct. 28, 1979. The neighborhood’s population dwindled, and its new residents did not have the spending power to support all of the area’s businesses, so many closed. In an effort to reduce blight, the city began demolishing empty homes. Arson took others, leaving behind a patchwork of trash-ridden urban prairie.

Despite this depressing picture, community groups including Broadway-Fillmore Alive and the Central Terminal Restoration Corporation are promoting historical preservation and the neighborhood’s rebirth. Planned events for 2010 at the old railroad station include a train show and autumn picnic. Thousands of partygoers packed the concourse for an April Dyngus Day celebration featuring live music, sausage, pierogi and beer.

Taylor says that in the past, Buffalo has not had the “innovative and creative thinkers” to revive its historical landmarks the way many other cities have: “Buffalo never figured that out, and they’re not close,” he says. Nevertheless, he believes the East Side has “not seen its last fine days.” The best plans for revitalization, he says, will focus on improving the fabric of a neighborhood — the housing, the commerce and the schools — and not just on developing a single resource. In his opinion, the East Side’s decline happened because of “a series of choices and decisions” that politicians and citizens made.

“We did this,” Taylor says. “We chose this,. And as a consequence, we have a chance to make a better decision, to make better choices…We’ve got a chance to fix it and a chance to make it better, so that’s our destiny. And that’s why I like it.”

Ruins | Charlotte Hsu

Charlotte, the author of this story, works in the University at Buffalo’s communications office. This blog is independent of her job at UB, and she had not met Henry Louis Taylor Jr. prior to reporting for this article.

I just bookmarked this site, I really enjoy the writing style and am fascinated with Buffalo history. My one problem with this article however is that it does not mention the astronomical increase in heinous crimes and the overall lowered quality of living that ultimately forced most residents out of the East Side. Other than that I found Gates diagnosis to be quite succinct.

Thank you for the thoughtful comment, and apologies for my oversight in not mentioning crime. Notes like these help to complete a story.

I grew up in Buffalo and remember how beautiful this district was. I used to love walking through the Bway/Fillmore district and shopping there. The decline of Buffalo’s once diverse and thriving East Side was the reason I left. ….Recently, due to unfortunate circumstances, I found myself ‘stuck’ in this part of Buffalo for an entire year. It was the most depressing year of my life. ….

The Bway/Fillmore area is horrible, with its rat-infested boarded up buildings and zombie-like crack addicts teeming the streets. The entire East Side is no better with the complacent ‘who-gives-a-cr@p attitute of the residents. …My folks were struggling and black, yet they instilled a sense of pride in my community and caring for my property and for the things I own; no matter how little.

I’m sorry, but I have no sympathy for folks who don’t take care of their place of residense, much less themselves. …I was so disillusioned with my former hometown, it was pathetic.

Thomas Wolfe was so right… “You can’t go home again.” NEVER.

Nothing will help this city.