AMHERST, N.Y. — The winemaking rituals are an heirloom from the Old Country, an artifact of the world Luigi Aloisio left behind when he sailed for America in 1939.

Every step is labor-intensive, from the washing and tightening of heavy, oak barrels to the stemming of grapes. The recipe is simple, requiring no sugar, yeast or chemicals beyond those occurring naturally in the fruit.

Luigi brought these methods to Buffalo from San Pio, the small town folded into the foothills of Italy where he grew up.

He came to the United States as a teenager. But like many Italians arriving in Western New York in those days, he did what he could to preserve the ways of the Old World in the new.

He grew basil and tomatoes in his garden on Grover Cleveland Highway. He hung legs of pink prosciutto in his basement. And every autumn for half a lifetime, he headed over to Desiderio’s on Bailey Avenue to pick up boxes of moscato and alicante grapes to press into wine.

Where they kept the wine | Christina Shaw Photography

Now, at 88, Luigi is bed-bound in the veteran’s hospital. His mind is fragile, his body weak.

But even when he is gone, a part of him—and a part of Italy—will survive through the craft he passed on to his son-in-law, Ray Fashana, 55, and grandson, Charlie Fashana, 29.

For the past few years, with Luigi’s health failing, the Fashanas have made wine from juice instead of grapes. But Charlie, an HSBC marketing manager, recently purchased a home in North Buffalo and plans to devote the property’s cellar to the family winemaking operation.

Once he and his father set up barrels and other equipment, they will revive the old traditions—starting with the fruit.

For as long as Ray can remember, the winemaking began in late September or October, when the grapes arrived at James Desiderio Inc.

The men in the family would drive down to the East Side wholesaler to pick up 900 pounds of the fruit, which came in 36-pound boxes.

Then, in the cinder-block basement of the house that Luigi built, three generations—mothers, daughters, sons and fathers—convened for a day of stemming.

Plucked from their delicate spines, the fruits resembled gems, each exquisite, each bursting with color. A red wine mixed two boxes of dark alicante with 23 boxes of white moscato.

To coax out the juice, the men pressed the grapes twice—first by running the fruit through the wrought-iron wheels of a hand-cranked grinder, then by crushing the remaining pulp under heavy, wooden blocks.

An important attribute of the process was that nothing went to waste.

“We used to give the mashed grapes—after they went through the grinder and the squeezer—to one of my grandparents’ friends,” Charlie remembers. “They could take it and use it for [moonshine]. Even the mashed grapes got taken somewhere.”

Ray, left, and Charlie, with the squeezer | Christina Shaw Photography

The oak barrels that stored the fermenting wine were the same ones the family used for decades, taking care each year to tighten the metal hoops binding the vessels together.

The frugality was a product of the difficult times Luigi survived—first as a child of the Great Depression, and then as an immigrant building a new life.

In this and other ways, the making of the wine each year came to embody the family’s history. The drink was a taste of the Old World—of the Italy, both harsh and beautiful, that Luigi left behind in the first half of the 20th century.

In San Pio, where Luigi lived until his late teens, a walled castle overlooked a tapestry of narrow, brick streets cascading down the side of a hill.

The town, however picturesque, offered few opportunities for residents. Like their neighbors, the Aloisios lived in a tiny, stone house, with seven people crowded into three rooms.

On a small plot of land, they grew fruits and vegetables, along with grains that they brought to a mill to make flour for bread. They worked the soil by hand, with the help of a few mules, and ate nearly everything they farmed. Chickens provided eggs, and pigs a portion of meat on special occasions.

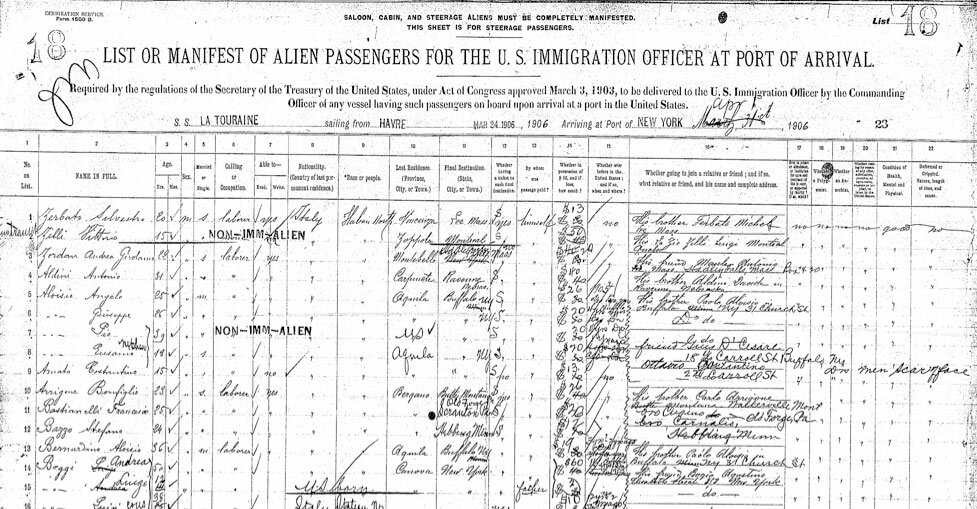

From this world, Luigi’s father, Eusanio, joined the flood of foreign workers pouring into the United States at the turn of the 20th century.

He arrived at Ellis Island in late March of 1906 aboard the steamship La Touraine. The passenger manifest identified him as a “laborer.”

His name appeared in the document among those of many other young men from Italy: Antonio Aldini, Stefano Bazzo, Umberto Davolio. Their destinations were places like Pittsburgh, Philadelphia and Detroit.

They were among more than 12 million immigrants who would enter the United States via Ellis Island between 1892 and 1954.

They came, as many before them had, in pursuit of a better future. In American factories, Europe’s peasants learned to smelt iron and assemble cars, filling the low-wage jobs that fueled the rise of the steel, automobile and other industries.

Eusanio found work in Buffalo, building bridges and roads in the bustling city that, just years before, had hosted the Pan-American Exposition. Like many of his compatriots, he began life in the New World alone.

Charlie, who recently interviewed his granduncle Carino about the family’s history, says Eusanio became a naturalized U.S. citizen after serving in the country’s military during World War I.

The rest of the family stayed in San Pio until 1938 and 1939, when Luigi and his brothers, Carino and Morfino, followed their father to America.

War was exploding again in Europe, and the siblings thought they would be better off in the United States, which was emerging from the Great Depression.

They settled in Buffalo, where many paesani—friends from home—had already regrouped.

Luigi was 17.

He went to school to learn new trades, but worked mostly at Lorenzo’s Bakery. A few years later, the United States entered World War II, and Luigi was drafted into the U.S. Army.

He had spent most of his life in Italy, an Axis power. His English carried a heavy accent. But when the military queried him about his allegiances, he responded, “I’m an American now.” He fought in invasions of Sicily and other parts of his home country. Injured in Europe, he received the Purple Heart.

The brothers. From left to right, Carino, Morfino and Luigi | Christina Shaw Photography

He made it back to Buffalo alive, and in boom years after the war, he partnered with Carino and Morfino to open Aloisio Brothers Concrete Company. They ran the business for 30 years, earning new clients by word of mouth.

As Carino would tell his grandnephew, Charlie, years later, the siblings were “an all-American family, straight from Italy.”

When Luigi built his house on Grover Cleveland Highway, with its gardens of basil and tomato and its cellar full of Italian wine, he hung the U.S. flag out front. He was proud of everything the New World had enabled him to accomplish.

One of the best things about America was how much of Italy a person could find and recreate in the country.

Luigi cured his own sausage, bought provolone at the deli, and invited guests—no matter the time of day—to sample the wine he crafted in his cinder-block cellar.

He made about 70 gallons of the stuff each year and doubled production sometime after 1979, when Ray married into the family and began to get involved.

In the tradition of the Old World, winemaking days at Luigi’s home brought loved ones together to share in fun and work.

There was always something distinctly old-fashioned to the proceedings, which Luigi initiated with a prayer.

“Lord bless this wine, bless these grapes,” he would say, making the sign of the cross.

The fruits the family pressed were of the same varieties that villagers in San Pio had stomped each year in rubber boots after the harvest. The fermentation method, all natural, was an Italian import.

Lunch was a feast, with a spread of Italian cheeses, peppers, eggplants and salted meats.

When Luigi was well, the family tasted the new wine on Thanksgiving and cracked barrels open on Christmas Eve. The batch would be gone as the next holiday season rolled around.

As Ray says, “You can’t make wine without drinking wine. That’s a sin.”

Charlie remembers how, when he used to cut his grandfather’s lawn, “I wouldn’t be able to leave until I had a drink.”

“We had a glass of wine in the mid-morning, after we’re doing work outside. Obviously, with dinner. It was just like drinking water with them. That would explain why so much of it went,” Charlie says. “It was just a regular thing.”

Where it all began | Christina Shaw Photography

Men of Luigi’s generation did things their children, who came of age in the New World, would never quite understand.

They saved everything—bits of string, scraps of wood—in case they might need it in the future. They kept track of pennies. On occasion, they could come off as stingy, leaving meager tips or walking long distances instead of taking a taxi, even when they could afford one.

Through Luigi’s annual winemaking rites, Charlie and Ray caught glimpses of this Depression-era mindset.

Every year for decades, during a break from stemming, lunch took place in a room that looked like a page out of a vintage catalog.

The table, chairs and refrigerator remained unchanged for so long that they became retro. When the men heated pots of grape juice to kick-start fermentation, they did it using an old Tappan stove.

Why replace what works?

The wine itself, through its lovely simplicity, seemed to say something about the world. Free of additives, the drink was pure, uncomplicated.

Charlie, who has been stemming grapes since he was 8 or so, imagines that he would like to be that way.

“My grandfather never had a credit card his entire life,” Charlie says. “He had a $5,000 mortgage on this house that he paid off…If the world followed that mindset, there’d be no recession of 2008. I admired where he came from, and what he stood for.”

Sitting in Luigi’s basement, sharing a glass of wine on a Sunday afternoon, Charlie and his father swap stories about the man they looked up to so much.

“He would save shoelaces, wire,” Charlie begins. “Just look around. You’ll see—”

“Light switches and knobs,” Ray interjects.

“If something just stopped working, he would save it up,” Charlie continues.

“…You’ll see things in this house [that have been here] for 50 years,” Ray adds.

“He would save a bulb off a Christmas light set to fix another set,” Charlie remembers. “He would never replace a Christmas light set. He would fix it.”

Charlie recalls one aphorism, in particular, that his grandfather used to repeat.

“Charlie,” Luigi would say, “I’m old. Would you get a new one of me?”

Of course not.

The philosophy, like the wine, was simple: Plain, no-frills, an heirloom from a world long gone.

Robert Salonga, a crime and public safety reporter for the Contra Costa Times in the San Francisco Bay Area, edited this story. A version of this story appeared as part of a suite of stories on wine in Buffalo in this summer’s edition of .

Pingback: old school wine makers. « Christina Shaw Photography

I learned to make wine from a high school friend’s Italian grandfather. He had a small farm house just outside a small town in Pennsylvania. He too brought skills with him when he emigrated from Italy. He had a spring house, where he would hang the various hams and homemade sausages. He had enough land to have several rows of grape vines and so he proudly made his wine from his own grapes. He showed me how the grape were really hybrids with Italian varietal grapes grafted onto American grape root stock. I was 17 when I first came for a month long summer visit and went back several times. For what ever reason the old man and I found each other’s company mutually agreeable and we spent a fair amount of time drinking his wine and enjoying life! Your story brings back his memory to me and for that I thank you!

Salute’ Pisan !!!

I have just went through your website. I am at present writing about my father from Italy, Tezze sul brenta and how he made wine back in 1920, 30 and 40’s. He had a home made wine press built on the basement floor, about 36″ round, cement and added the steel uprights much like your pictures show. The press was about 16″ or so, now much memory so I guess. It was turned by a long wooden post about 6′ long, the turnstile was round and had 4 upright steel rods into which he put the pole and turned it. What memories I have of that. The grapes believe it or not were a mere 5 cents a box ! (1930’s)we had to go to the rail yard (Chicago) to pick up the grapes. they were in wooden boxes about 16″ X 8′ and 4″ high. I am really guessing here. anyway, thank you for your photos and for the memory you have helped me remember.

Ciao ‘ geno loro