BUFFALO, N.Y. — In the shade of snakewood and trumpet trees, a new day is beginning in the indoor rainforest at the Buffalo Zoo.

Newly freed from the holding cage where he spends the night, Machado, a black howler monkey and father of two, is perched on a branch in a corner exhibit. His head raised, his mouth wide, he is calling out, as is his morning routine.

His cry—deep, unbroken, guttural—echoes through the 26,600-square-foot rainforest compound. The sound is audible from outside, too.

Wild howlers vocalize at dawn to claim their territory, and here, in the zoo’s more limited environs, Machado continues that tradition by announcing himself each day.

Elsewhere, residents of this tropical empire are slumbering, eating or building nests.

The forest’s inhabitants include Mojo and Haji, two giant anteaters who have been together for four years; Lola, a tiny sunbittern who fancies herself queen of this kingdom despite her size; and Argyle, a young saki monkey who recently taught his parents how to steal food from toucans.

On any given day, human visitors might pause to snap Mojo’s photo, or to watch Argyle tackle his mother to coax her into playing.

But few zoo patrons will spend enough time here to glimpse the exhibit’s true complexity. Enclosed beneath skylights, this place is a world of its own—separate, somehow, from everything that surrounds it.

In summer, warm rain falls at least six times a day, mimicking the wet season in the hot, lush Amazon. Temperatures remain tropical even on the coldest night of a white Buffalo winter.

Within these walls, life begins and ends.

Argyle was born here in 2010, two years after the exhibit opened. His parents came from zoos in San Antonio and San Diego, but Buffalo is his first home. It’s here that he is discovering the foods he likes and testing the limits of his strength and agility. He could live for another two decades, and the skills he is learning at Rainforest Falls are the ones that will get him through those years.

Of course, the zoo holds vastly fewer spaces for Argyle to explore compared with the open expanses of the South American rainforest where free sakis live. The exhibit area, with a total of 8,900 square feet for all the animal displays, can’t compare with the wild.

Holding wondrous, intelligent creatures in captivity raises questions of morality. The most ardent critics assert that zoos are just plain wrong, and activists have documented neurotic behavior in confined animals.

But while the debate rages in the outside world, life continues in Buffalo’s indoor rainforest. Like Argyle, the vast majority of the birds, beasts and reptiles in the exhibit were born in captivity. Few know the wild.

For them, this is home.

The Buffalo Zoo, formally the Buffalo Zoological Gardens, is more than 135 years old.

The city established the institution at the edge of Delaware Park in 1875 after receiving a pair of live deer from Jacob Bergtold, a local fur dealer.

Like many of America’s oldest zoos, Buffalo’s has undergone extraordinary changes in recent decades as ecological conservation emerged as a global priority. Evolving with the times, zoos have shifted their focus from simply entertaining visitors to preserving biodiversity through breeding programs and educating the public about the importance of protecting wildlife.

Over the past decade, the Buffalo Zoo has invested $32 million into improvements, with an emphasis on creating more natural habitats for animals, said Donna Fernandes, president and CEO.

M&T Bank Rainforest Falls, the zoo’s rainforest compound, exemplifies the new philosophy.

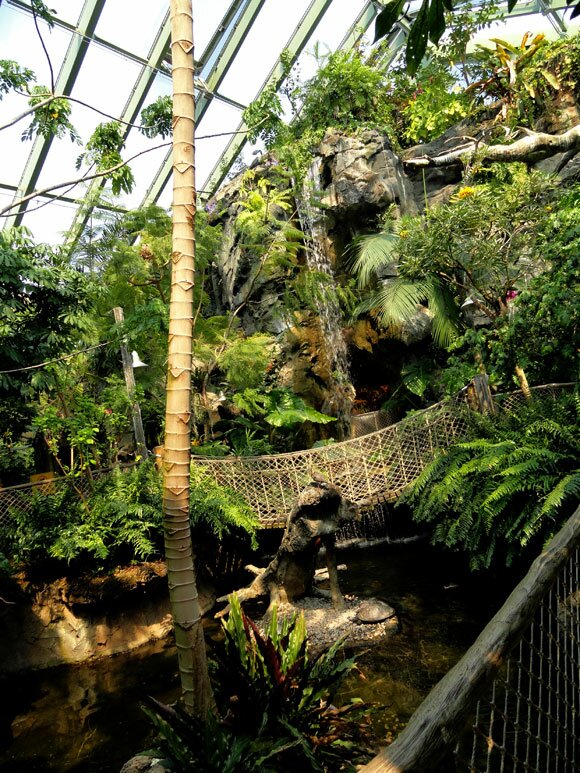

A two-story waterfall anchors the exhibit space, dropping from a rockwork plateau into a stream where dwarf caiman and river turtles share territory with a family of capybaras, hog-shaped creatures that are actually the largest rodents in the world.

Curtains of enormous, burgundy calico flowers sway lightly as visitors stroll past. Hot, wet air kisses the skin. Overhead, birds including red-feathered scarlet ibises flutter by, free to fly between areas that include the anteater enclosure and the stream banks where the capybaras reside.

The architects and builders of this artificial rainforest modeled it after the warm, wet landscape surrounding Venezuela’s Angel Falls.

The intricacies of the design, from the voluptuous vegetation to the daily rains, mimic the real thing. Skylights in the roof are made from a plastic membrane that blocks unwanted heat while letting in ultraviolet light, which plants and animals need to synthesize vitamins.

In a Q&A in Buffalo Spree magazine in October 2008, the month after Rainforest Falls opened, Fernandes discussed the motivation behind creating such a complicated, immersive exhibit.

“The role of zoos has changed over time from menageries designed to amuse visitors to centers for wildlife conservation designed to educate visitors about the plight of endangered species and the role we can play to protect the environment,” she said. “Rainforest Falls is a wonderful replica of a unique and fragile habitat that will help us teach children about rainforest diversity and conservation.”

A Lush Land

The caretakers of Rainforest Falls include Steve Mead, the zoo’s director of horticulture and maintenance, and Dave Goehle, zoo groundskeeper.

Check out our Q & A with these gentlemen, who took the time to tell us a little about what it takes—behind the scenes—to keep the exhibit’s greenery healthy.

Through the enormous, holed leaves of the swiss cheese plant, scientific name monstera deliciosa, the day’s first human visitors are watching a rivalry unfold: giant rodent versus bird.

On the bank of the stream that runs through Rainforest Falls, a young capybara is struggling to hold ground against the prodding beak of a scarlet ibis that has landed, presumably, for a drink.

It’s a strange sight: the roly-poly capybara—tottering on its odd, webbed feet—tussling with the elegant, thin-necked bird.

Elsewhere in the compound, another confrontation is taking shape.

Two brothers are squabbling. Hanging upside down from his tail, Chaka, the zoo’s youngest howler monkey, has managed to thread his hands beyond his enclosure’s netting to grab some food.

Unfortunately for Chaka, the branch of tasty leaves he has grasped has caught the attention of his older brother, Mochima.

Chaka, sensing his brother’s desires, clambers higher in the exhibit, twisting and turning to keep his cleverly-earned bounty away from Mochima’s greedy hands. But Mochima is fast. He snatches a few leaves and stuffs them immediately into his mouth.

Chaka can’t be happy. But soon, in the manner of siblings, the two will be getting along again, resting side by side on the same tree limb.

They are different from us, the animals. But in their lives, we see bits of our own reflected: affection, desire, frustration, anger, curiosity.

This much is clear at Rainforest Falls, where human companions hold hands while peering in on monkeys grooming each other.

On both sides of the partitions that separate human from animal, parents keep a vigilant watch on sons and daughters. During Labor Day weekend, a particularly sweet moment transpired in the central wetland exhibit, where a large capybara gave a helpful nudge to a tiny cub flailing in a failed attempt to surface from stream to bank.

Barriers may define this place, but they can’t obscure what we have in common.

The day begins in Rainforest Falls long before the zoo opens at 10 a.m. What visitors see is only a small part of what goes on.

Behind the scenes, the exhibit’s complicated machinery includes three filtration systems that control the artificial waterfall, as well as the water that refreshes the stream and a tank holding a 13-foot anaconda.

At night, when keepers are away, a high-tech environmental system monitors conditions within the compound, sending out an alert if the temperature or humidity falls or rises beyond of the normal range.

The rainforest’s guardians also include an army of amphibians. Free to roam the grounds as they please, red-eyed and hourglass tree frogs comb the exhibit and an adjacent greenhouse for bugs. With the space housing dozens of different types of plants, it was nice, said keeper Pamela Harmon, to find a “natural” solution to the pest problem.

Harmon, the zoo’s avian collection manager, leads a team of several keepers who care for the inhabitants of Rainforest Falls.

Each day, the first of these humans reports for duty at 6 a.m. Morning responsibilities begin with scrutinizing the exhibit area to make sure all animals are healthy and uninjured. The survey also covers smaller holding areas where many of the creatures, including the primates, sleep.

Holding rooms | The Buffalo Zoo

Later, keepers divvy up a range of tasks, from cleaning cages to introducing new animals to one another.

Meal preparation is a huge and sometimes bizarre job. Most species get a biscuit-based diet that matches their nutritional needs, but others have more distinctive tastes.

A freezer and refrigerator in the rainforest’s kitchen hold a cache of gory treats: tiny mice called “pinkies” for the pirahnas, slightly larger mice called “fuzzies” for the cattle egrets, and day-old baby chicks for the ocelots, a forest cat. Now and then, a box of blood will arrive at the compound for the vampire bats.

From diet to the environment to relationships between animals, life at Rainforest Falls is tightly controlled. Feeding times are regular, as noted by Hahm, the male armadillo, who emerges from his burrow at around 2:30 p.m. each day to retrieve his family’s meal.

Living arrangements are also strict. Dwarf caimans (which look like small crocodiles) can share an enclosure with the capybaras because even the smallest of the rodents is too large for the reptiles to threaten. The toucans, on the other hand, are extremely aggressive and must reside in an exhibit apart from other birds. Nothing, it seems, is random.

But, as Harmon says, that doesn’t mean the rainforest doesn’t hold surprises. She recommends that visitors take a close look: “It’s just a matter of spending time in the exhibit, and coming back at different times,” she said.

Within their highly restricted environment, it’s often the animals who dictate the terms of life.

Keepers would like Cheech and Chiquita, a pair of 7-year-old male and female chestnut mandible toucans, to breed. But the birds have decided to take it slow. Cheech sometimes brings food to Chiquita—a sign that he’s interested in her—but so far, the two haven’t mated.

In the same enclosure, Argyle has outsmarted his human overlords. Before he was born, Harmon and her crew were able to feed the toucans by placing a small pan of food in a location at the back of the exhibit that Argyle’s parents, Katrina and Maracaibo, couldn’t reach.

But Argyle, in the explorations of his youth, figured out quickly that an uninhibited jump or two could get him to Cheech and Chiquita’s stash of bananas, blueberries and papaya. Now, he stops by regularly to get his fill. His parents, seeing his success, have followed suit. The humans haven’t been able to find a better location for the toucans’ dish, so the intrusions have simply become part of daily life.

Life in the artificial river | Charlotte Hsu

As for who’s really in charge of Rainforest Falls, Harmon talks lovingly of Lola, the inquisitive and commanding sunbittern, who was one of the first residents.

“Lola came in, and she was released out into the exhibit with several free-flighted birds,” Harmon said. “So she kind of got used to the entire exhibit before everybody else did, and now she kind of considers herself the queen of the exhibit. She’ll make sure everyone’s in check and where they’re supposed to be.”

When new animals arrive, Lola will stick her head in their crates to see what’s happening.

“She is only a hundred-gram-sized bird, yet she’ll threaten,” Harmon said with a laugh. “If there’s something new in the exhibit, it’s a guarantee that she’ll be there in a matter of minutes to check it out. Sunbitterns are very territorial.”

The cast of characters inhabiting Rainforest Falls is always changing, as Lola has seen.

When the exhibit opened, zoo officials populated it mainly with animals born in captivity. Exceptions included the anaconda and Haji, the male anteater, both of whom were imported from the wild by other zoos. The dwarf caiman, also originally wild, came to Buffalo through a reptile dealer.

Since then, Harmon and her team have watched as families have formed and grown in the indoor rainforest. Besides Argyle, Chaka and Mochimo, the exhibit’s newborns have included scarlet ibises, boat-billed herons, cattle egrets, roseatte spoonbills, yellow-crowned night herons, vampire bats and six banded armadillo.

Mama and Papa, the zoo’s two adult capybaras, have been particularly prolific. Since meeting in 2007, the pair has produced eight litters of babies.

Rainforest Falls can’t hold all these offspring, so the zoo has donated them to other zoos and animal parks in more than a dozen U.S. and Canadian cities. Recipients have ranged from the Toronto Zoo and Biodome de Montréal to the Denver Zoo and Tennessee Safari Park.

Harmon says the departure of the juveniles, who are shipped off after showing signs of independence, doesn’t seem to be an emotional experience for the parents; they behave no differently when the young are gone. But for the human keepers, saying goodbye isn’t easy.

“They will follow us around. … We get really attached to them because we hand-feed them,” Harmon said, noting that the rodents have a gentle, pet-like disposition.

“With them, we’ll whistle, and they’ll come,” she said. “So they have a giant dog personality.”

Other farewells are yet more painful.

Death has taken some of the compound’s residents, including a sunbittern whom keepers found dead with no clear cause. A blue-crowned motmot landed on the mesh shielding a monkey exhibit, and later perished from wounds that one of the primates inflicted. In another accident, a scarlet ibis met its demise when it crashed into a window, even though staff had soaped the barrier to help the birds see it.

In addition, as of late August 2011, animals that died of natural causes included a female tamandua, some pirahna and a few newborn bats, according to Fernandes and Jean Miller, the registrar for the zoo’s animal collection.

But life goes on despite the losses. New animals join the compound. Old friends go. Chaka and Mochima, the two young howler monkeys, departed for the Wildlife World Zoo this June. As in nature, the rainforest is ever-changing, never staying the same long.

Outside, winter is coming. Cold winds have begun to blow across the city. Frozen puddles gleam like mirrors in the streets, waiting to be cracked by the tip of a toe, like crème brûlée.

When the weather turns white, the keepers of Rainforest Falls will bring in tubs of snow for the monkeys and anteaters, who will forage through the powder to find snacks buried below.

But otherwise, the world inside will remain hot and lush, beating to a tropical pulse at odds with the Buffalo winter.

Machado’s cries will fill the compound every morning. His “wife” will join in. From across the exhibit, Cheech and Chiquita will croak back. The dwarf caiman, who are most active at night, will settle into a comfortable spot in the stream to rest. Spoonbills, egrets, and scarlet ibises will swoop down for a quick drink before shooting back up into the canopy.

Somewhere, Lola will be keeping an eye on everything. And in this way, another day will begin.

Robert Salonga, a crime and public safety reporter for the San Jose Mercury News in the San Francisco Bay Area, edited this story. Many of the scenes and photographs from the article are from 2011, when the primary reporting for this story took place. We were unable to publish the story until now due to one of our main sources being unavailable to check facts earlier. We are sorry for the delay.

Wonderful story, Charlotte. Makes me want to visit.

(And I’m one of those people who HATE small zoos.)

Thanks, Hugh =). Glad you enjoyed it. Here’s the story from the Tampa Bay Times that inspired this one: http://www.sptimes.com/2007/webspecials07/special_reports/zoo/.

Of course, our story wasn’t anywhere near as complete/complex as the TBT piece, which is a wonderful (but very long) read.

The opening lines: “Eleven elephants. One plane. Hurtling together across the sky.

The scene sounds like a dream conjured by Dali. And yet here it is, playing out high above the Atlantic.

Inside the belly of a 747, 11 elephants are deep into a flight from South Africa to Florida. These are not circus elephants, accustomed to captivity. All are wild, plucked from game reserves in Swaziland. All are headed for zoos in San Diego and Tampa.”

I’d like to go visit the rainforest with you! You know all the inhabitants by name! One thing I really enjoy about Florida is the birds. The roseate spoonbills are amazing and I love the big birds like the pelicans, sand cranes and herons. Last year I even saw manatees ( which, I realize, are big but not birds).

Seriously, I loved the story. Although I have visited the rainforest exhibit, I missed a lot and look forward to going again.

Thanks for the zoo article. We haven’t been there in quite some time. I would like to go with you and Zak some nice day this spring. Keep on writing.

Mike Burns