BUFFALO, N.Y. — It was like a vision out of a dream: strange and unexpected. Unreal.

In 1965, Robert F. Courter Jr. flew an office chair. It was an ordinary, run-of-the-mill seat — except for the tanks of rocket fuel that engineers had rigged to the back.

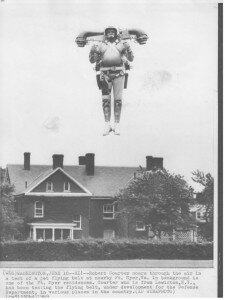

Before launching, Courter donned a white flying suit, helmet and sunglasses. Then, he blasted off, rising into the air with a puff of vapor. An old black-and-white video shows him floating up and forward, his trajectory a long and graceful arc.

Robert Courter, ready to fly | Courtesy of Bell Helicopter Textron, from the collection of Steve Lehto

The chair was maybe the oddest contraption that Courter helmed in his career as a test pilot.

But others he mastered were no less astonishing. At Bell Aerosystems Company in Western New York, he led a team of men who sailed over fairs and football games in the rocket belt, the device made famous by the James Bond movie “Thunderball.”

Later, Courter pioneered the jet pack, along with a bucket-shaped hovercraft called the WASP.

It was the space age. Astronauts were heading to the moon. The government was building planetariums in schools. Technology was taking America new places, and the possibilities felt limitless.

Courter’s work was a part of that ambitious era. His story and that of his family are an integral part of Western New York’s aviation history.

Perhaps more than any other person on Earth, he came close to fulfilling the human fantasy of flight — not the kind where you crawl into the cockpit of a plane, but where you step outside, look up and simply take off.

Half a century after Courter flew them, the rocket belt and jet pack still inspire wonder: How could a person conquer the sky like that, devoid of baggage, without even wings?

One of four surviving Bell rocket belts resides at the University at Buffalo* | Douglas Levere, University at Buffalo

That was the headline on a first-person essay by Courter that appeared in Popular Mechanics in 1964. On the first page, he described the wonders of flight:

“I throttle the power on full, for nearly 300 pounds of thrust from pressurized fuel tanks. The roar is deafening as the twin rocket nozzles, spewing an invisible hurricane of steam, thunder to life. Dust billows around me — kicked up by the thruststream.

“Its blast is more powerful than a fire house. The harness strains, gives a tug and I feel myself lifting. In that split-second of take off, it’s as though some giant put a hand beneath my arms and another where I sit, jerking me off my feet.

“In an instant, I’m airborne. Next, I’m flying like the birds.”

“We both shared the same feelings about flight. It’s a separation from everything you deal with on the ground. The sights are beautiful from that altitude.”

— Stephen Aicholtz, son-in-law of Robert F. Courter Jr.

Then comes an astounding prediction: “If my voice could punch through the rocket’s thunder, I’d tell anyone who listened: ‘In 10 years, maybe less, some of you will be up here flying with me.'”

The rocket belt was the first of the so-called individual lift devices that Bell built and Courter tested.

The contraption consisted of three tanks strapped to the pilot’s back, as author Steve Lehto recounts in his book, “The Great American Jet Pack.” Two of the canisters held hydrogen peroxide (which, in a highly concentrated form, serves as rocket fuel). The third contained pressurized nitrogen, which pushed the peroxide over a catalyst that caused the chemical to explode into steam, which bore the wearer aloft, Lehto writes.

The design was elegant and clean: Rocket belt aviators looked like airborne scuba divers — at 30, 50 or 60 feet aloft, they had no wings, no propellers and no platform to stand on. To control motion, the pilots simply leaned in one direction or another (as with a Segway on land). To spin, climb or descend, they operated controls on chest-level handlebars.

The resulting movement looked slick and gentle — the mysterious gliding of a hovercraft — and it mesmerized the public.

“I do remember seeing him fly a couple of times and thinking it looked — surreal. It just didn’t look possible.”

— Deborah Courter, daughter of Robert F. Courter Jr.

Still, Lehto wrote, the rocket belt had an Achilles’ heel: The device could only carry enough juice to keep the user airborne for 21 seconds. Adding more fuel to the tanks would increase the weight of the 110-pound gadget, cutting down on comfort and motility.

With this in mind, Bell engineers started work on the jet pack, a man-rocket that looked like the rocket belt, except that it used a turbojet engine in place of rocket propellant for power, Lehto said. The hope was that this configuration would yield longer flight times.

Courter bought into this dream. Though the military bankrolled Bell’s jet pack and rocket belt programs, he and others on the development team anticipated a grander, more popular fate for individual lift devices. “One in every garage” was the mentality.

In Popular Mechanics, Courter foresaw firefighters using the man-rockets as “seven league boots” that could “whisk them, in seconds, to within reach of a skyscraper’s loftiest holocaust.”

Surveyors could use the backpacks to cross rivers and climb hills, soldiers to bypass minefields, anglers to access back-country fishing sites, and commuters to zip over crowded roadways, Courter wrote.

In the mid-20th century, Western New York firms employed men and women to build and test all manner of remarkable contraptions, from the Bell X-1, the first jet to break the sound barrier in regular flight, to the Curtiss Warhawks that the Allied Powers piloted in World War II.

For employees of the region’s aeronautics industry, life outside of work was pretty much just like anyone else’s: They had children, they drank at local bars, they visited Niagara Falls in summer, and they shoveled snow in the winter.

The concerns of their families were equally typical: Courter’s wife, Phyllis, says the most difficult part about being the spouse of a rocket belt pilot was not the fear that some freak accident might happen, but the challenge of running a household alone.

To drum up support for the belt, Bell sent a team of pilots around the globe to perform at fairs, festivals and sporting events. As a result, Courter, the squad leader, was away from home for long periods of time, leaving Phyllis, an elementary school music teacher, to handle the couple’s two young kids.

“When they realized the rocket belt was a success, they decided that they wanted to promote it, so they hired this guy who was a real go-getter and he got the team going all over the world — not just the United States — and this went on for a couple of years,” Phyllis remembers. “It was a pretty hectic life for those guys that flew it.”

From a practical standpoint, “It was hard for me, because I was suddenly having to do everything, mow the lawn and fix plumbing problems,” she said.

She can’t recall exactly how long this went on, but “it seemed like forever.”

That doesn’t mean she wasn’t happy for her husband.

The two had met in eighth grade in Youngstown, N.Y., a small town north of Niagara Falls. She spotted him in school: He was the new kid, a boy with a fun personality, green eyes and Brylcreem in his dark hair.

Robert, Bob to friends, was handsome, but little about him hinted at a man willing to take unusual risks. He was quiet around strangers, and the activities he enjoyed were those that required calm and patience: fishing, hunting and, later, birdwatching with Phyllis.

“He was usually quiet. He didn’t fit the movie stereotype of a daredevil at all. He liked to read a lot. … He would go fishing every chance he got, he was a conservative Republican, and he was a quiet guy.”

— Stephen Aicholtz, son-in-law of Robert F. Courter Jr.

Flying, however, was Bob’s daredevil passion. He fell in love with it in high school, when a relative took him up in a plane. He trained as a pilot in the U.S. Army at the tail end of World War II, became a flight instructor, and later headed overseas to Korea to run missions in a P-51 Mustang for the Air National Guard, according to Lehto.

Along the way, Bob became good friends with Bell Aerosystems engineer Wendell Moore, the rocket belt’s inventor. Moore was the classic tinkerer, a man with wild ideas and the brainpower to realize them: “People used to say about Wendell that he’s always somewhere up there in the clouds, thinking,” Phyllis said.

When Bell offered Bob a job as a test pilot for Moore’s man-rocket, the Courters were elated.

“I knew about the device, of course, because we knew Wendell, and I knew how [Bob] loved to test-fly things and learn how to fly new things, so he was very happy, so I was very happy for him,” Phyllis said.

The rocket belt was a weird thing to fly — not just your “same old something or the other,” Phyllis said.

But she wasn’t overly concerned. Her husband was an experienced aviator, and Bell trained pilots on a tether before letting them go into free flight.

Deborah Courter, 62, director of human resources for the Health Federation of Philadelphia and Bob and Phyllis’s daughter, speaks of her father’s occupation with similar levelheadedness, bringing the conversation, if you will, back to Earth.

Deborah thought her father’s vocation was “neat,” something her classmates knew and talked about. But she also remembers being “much more interested in what I was wearing to school than what my dad was doing at the time.”

As for fear or anxiety over what others might qualify as dangerous activity, Deborah felt the same way as her mother: “I don’t remember being scared,” Deborah said. “I mean, I don’t remember thinking it was something he could hurt himself doing. I guess I just thought he was good at it, and he would be OK.”

It’s not that Courter’s family members didn’t recognize the extraordinary nature of what he was achieving.

Deborah characterized her father’s job as “something completely different from most people’s,” and “just so totally out of anybody else’s experience.”

“Where we grew up, people were farmers mostly, or they worked in the plants in Niagara Falls,” Deborah said.

He thrilled audiences with the rocket belt at the Paris Air Show, the New York World’s Fair and Super Bowl I in 1967 at Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum.

“Bell got very crazy at one point — this was when they were still trying the rocket belt and thinking what else they could fly — and Bob made a remark and said, ‘I think I could fly a chair.’ And so they did.”

— Phyllis Courter, wife of Robert F. Courter Jr.

Phyllis remembers the first time Bob piloted the flying chair, winning a bottle of whiskey from a colleague who bet that the feat could not be done.

Bob “flew some very strange things,” she said, laughing. After the chair, “he flew something called the pogo stick, which was like — I don’t know how to describe it — but it was like being on a stilt,” she recalled. (As Lehto writes in his book, the Bell Pogo was actually a two-man, flying platform made from two rocket belts attached to a Pogo stand.)

Bob’s stunts and adventures were so unusual that memory and myth mix in the retelling.Deborah thought her father flew the rocket belt for the James Bond movie, Thunderball, but the pilots who stood in for Sean Connery were actually Bob’s colleagues, Gordon Yaeger and William Suitor.

She also remembers her dad flying an individual device over Niagara Falls, but Phyllis doesn’t recall such an exploit. Instead, she remembers her husband zipping over the rapids above the cascade, from Goat Island to the American shore. Barry Virgilio, an educator for New York State parks, said he viewed a film clip documenting just such a feat. And Bell pilot Suitor, who still lives in Youngstown, verified that Courter made the flight.

What was inarguably true was that Bob, Moore and the rest of the rocket men were doing something extraordinary.

At home, they were regular guys: Bob, the husband and father who loved camping, canoeing and being outdoors, and Moore, who often dined and played cards with the Courters, and who would pop in to check on Phyllis when Bob was on tour.

But at work, the team was making history. In a turbulent time in America, with the menace of nuclear war looming and high-profile assassinations rocking the country, Bell’s engineers, builders and test pilots stood for what was good about the 1960s.

They were men of an era of huge technological promise, of an age when Americans dared to dream big.

The machines that U.S. scientists designed — from the spacecraft that carried Buzz Aldrin, Neil Armstrong and Michael Collins moonward to the humbler rocket belt that Bob piloted on Earth — were innovations that made the country proud.

The inventions belonged to everyone.

Of course, the dream of the individual lift device never became reality.

We don’t strap on tanks of rocket fuel or turbine engines for the commute to work. Helicopters, not jet packs, are still the mainstay of search-and-rescue missions. To reach isolated hunting grounds, sportsmen must still brave meandering journeys along rough-hewn roads.

Bob, who died in 2013, remains one of the only people in the world who ever experienced personal flight.

“They thought it would become the kind of device that you and I could fly at some point in its development. And who knows, it might still happen.”

— Phyllis Courter, wife of Robert F. Courter Jr.

After Bell gave up on man-rockets, he followed the individual lift device program to Michigan, where a firm called Williams Research was tweaking a machine called the Williams Aerial Systems Platform.

The WASP, as it became known, resembled a rounded podium and could stay aloft for about 10 minutes — 20 times better than the rocket belt, but still too brief to be useful.

The company shut down development efforts, and Bob retired. He and Phyllis moved to a quiet area of Michigan, where they lived on a lake, and then to a similarly serene location in Maine to be closer to their kids. They wintered in Venice, Fla. She enjoyed Audubon birding. He played golf, fished brook trout and retained membership to conservation clubs.

Phyllis thinks the last time Bob flew may have been in the 1980s, when he piloted a private plane to New York State for one of her parents’ funerals.

Looking back on his career and the evolution of the individual lift device, “I think he was very disappointed that the program ended with the WASP II, because the WASP II really was the thing that was on the edge of practicality,” said Lehto, who interviewed Bob for hours by phone in 2012.

“He flew more of these devices than anybody, and he mastered them all,” Lehto said.

Today, enthusiasts continue to construct gadgets from homemade rocket belts to engine-powered wings that you fasten to your back.

Here in Western New York, where it all began, you might spot adventurers hovering over Lake Erie courtesy of a Jetlev, a backpack that pushes two powerful streams of water downward to propel the wearer into the air.

True individual flight may never be possible the way Bob and others at Bell imagined it.

There are too many problems, and of all of them, this one seems the most intractable to Lehto: What if you lose power mid-flight, and you’re too high up to fall safely, but too low to pop open a ballistic parachute?

“You suffer what engineers call lift degradation, which is what happens when you take a rock and you drop it,” Lehto said.

“You plummet, and you die,” he said.

Still, no matter how daunting the technological obstacles, the dream of flying that began with pioneers like Bob and Moore may never be erased from the human psyche. Watch children sprint around a field, and you’ll eventually see one of them spread out their arms like wings, Lehto says.

A huge, blue sky awaits.

Charlotte Hsu was the author of this story. She works as a media relations manager at the University at Buffalo, but this story is independent of her work there. Robert Salonga, a crime and public safety reporter for the San Jose Mercury News in the San Francisco Bay Area, edited the article.

Special thanks goes to author Steve Lehto, who put us in touch with the Courter family. Lehto’s obituary of Courter and Lehto’s book, “The Great American Jet Pack: The Quest for the Ultimate Individual Lift Device,” were instrumental in helping us identify sources of information such as Bob’s Popular Mechanics essay and the video of Bob piloting the Bell flying seat.

Today, Bell Aerosystems lives on as Bell Helicopter, a division of of the company Textron.

Working as a volunteer at the Niagara Aerospace Museum, home of Bell Aircraft/Bell Aerosystems and Bell Aerospace the history of the rocket belt and the many contributions made by Bell in general to avaition and aerospace are phenomal and not always appreciated. Thanks for the article.

Good and exact story with a correct timeline.

Peter

Hi Char:

Nice article. A lot of people don’t know about WNY’s great aeronautical history. thanks for the info.

Mike Burns

Mike is right about this area having a great history of innovation. The father of a high school friend of mine worked at Scott Aviation in Lancaster and was a co-inventor of the Scott Air Pack. A similar device is used universally by Fire Fighters world wide. I always enjoy the character development and humanity that you bring to all your stories.

Pingback: The Man Who Could Fly: Robert Courter and the Bell Rocket Belt | Niagara Aerospace Museum

Pingback: Google’s 10 Zaniest Projects in the 10 Years Since the IPO | Tech-RSS.com

Pingback: Google’s 10 Zaniest Projects in the 10 Years Since the IPO | Re/code

Pingback: Google’s 10 Zaniest Projects in the 10 Years Since the IPO | HudRock Digital Media

Pingback: Genetic Engineer George Church Plans to Bring Back the Woolly Mammoth | Re/code

Pingback: The Time Traveler: George Church Plans to Bring Back a Creature That Went Extinct 4,000 Years Ago | The Global Point

It’s nice to see an article featuring the rocket belt that is accurate. I have read many articles online that did not give robert courter proper credit. My grandfather and father know Mr. Courter from the 4f club in niagara county and growing up i have heard plenty of fascinating stories of his adventures.

Pingback: Meet the Time-Traveling Scientist Behind Editas, the Biotech Company Going Public With Google’s Help | Re/code